Market Report - Instapoets and the Rise of Online Poetry by Emily Gough

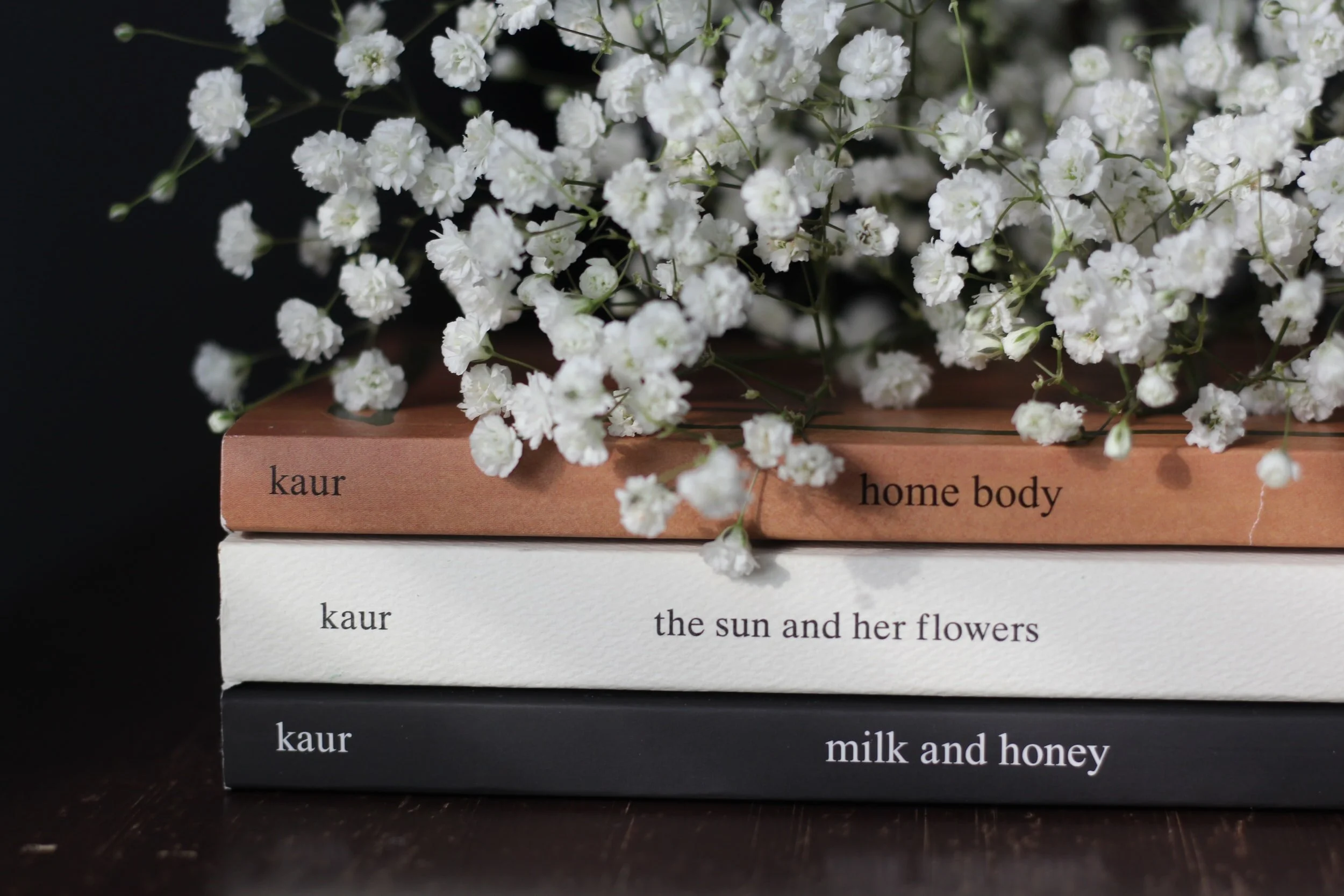

Image from Unsplash

Poetry is a long standing, multifaceted corner of the literary world that spans across thousands of years of human history, with ‘The Epic of Gilgamesh’ widely considered to be the first poem ever written and dating back to the 18th century BC [1]. Of course, this does not take into account the rich history of oral poetry that came before, but it is perhaps a combination of the spoken and written forms of poetry that have ensured the genre’s persistent survival and it’s many revivals. One of these revivals has taken on a less traditional form in more ways than one as, in an age where social media is so widely used, many artists and creators have taken to sharing their work online, and poets are no exception.

With Instagram’s insights boasting one billion monthly users in 2018, writers such as Hollie McNish, Nikita Gill, and Tyler Knott Gregson have all gained thousands of followers and a strong audience for their work by uploading it to the platform, paving the way for what has since been dubbed “Instapoetry” [2].

A portmanteau of ‘Instagram’ and ‘poetry’, Instapoetry is a contemporary subgenre stylised by fragmented free verse poems usually set alongside a simplistic line drawing or laid over an image; Indian-Canadian poet Rupi Kaur is generally seen as the pioneer of the genre, in part due to her prolific number of achievements with her poetry. Currently claiming 3.9 million followers on Instagram, Kaur originally self-published her first poetry collection milk & honey in 2014, but it was quickly picked up and issued in print by Andrews McMeel Publishing. The collection landed on the New York Times’ best sellers list and remained there for ‘more than 100 consecutive weeks’, selling over 3 million copies and eventually ‘stealing the position of best-selling poetry book from The Odyssey’ [3],[4]. Her second collection, 2017’s the sun and her flowers, sold over a million copies ‘within the first three months’ of publication. For a debut poet and an internet subgenre that branched from a typically traditional literary form, these achievements are unprecedented [5].

However, controversy began with scattered debates over whether Instapoetry could be classed as “real poetry”, and Twitter users and Goodreads reviewers alike could be seen mocking the fragmented sentence structure and form. But, the debate erupted when poet Rebecca Watts published a scathing article in PN Review refusing to review Hollie McNish’s poetry, calling the movement ‘artless’ ‘consumer-driven content’ that panders to ‘instant gratification’ [6]. Yet, despite this negative backlash, Instapoetry has made huge strides within the publishing industry and has had an impressive effect upon poetry sales, with an article by The Bookseller noting that ‘[2017] marked the best sales on record for poetry books in both volume and value, driven by a new appetite for the work of living poets with strong online followings’ [7]. Similarly, The Guardian states that ‘1.3m volumes of poetry were sold in 2018, adding up to £12.3m in sales’, remarking that Kaur’s milk & honey reportedly made up ‘almost £1m of sales’ [8]. The article also mentions that ‘[t]wo-thirds of [poetry] buyers were younger than 34 and 41% were aged 13 to 22’, correlating with Instagram’s demographics which currently show that 65% of overall users are between the ages of 18 and 34, thus providing the perfect breeding ground for new poetry readers and acting as an effective marketing tool [9],[10].

If these burgeoning market statistics are anything to go by, online poetry is not only innovating the genre at large, but it is also innovating the publishing world and the way that readers consume poetry. As such, Instapoetry has been praised for bringing poetry to a wider audience, perhaps an audience who may have previously perceived poetry as ‘the literary equivalent of opera or ballet, a privileged-white-male establishment hostile to their interests’ [11]. The online content is more accessible, particularly to audiences who do not consume traditional poetry, and the platform allows poets to continually engage with their audience whilst keeping up to date with current topics, trends, and events.

Rupi Kaur and her peers exemplify this, as they explore many relevant issues in their poetry, such as resilience, relationships, self-love, and many topical and contemporary discourses, or ‘shared themes’, that are being held online: ‘anger at how the world treats young women, especially women of colour; defiance in the face of dismissal; celebrations of modern femininity’ [12]. Perhaps, then, by portraying their open and honest emotions on visual platforms mostly known for consumerism and narcissism, these authors are making poetry more relatable to their audiences, although the ‘landscape leaves some wondering to what extent this is an exercise in poetry and to what extent an exercise in producing visually engaging, relatable content for as wide an audience as possible’ [13].

In any case, the poetry scene does not appear to be slowing down, with readers and poets alike calling the recent upsurge ‘a genuine renaissance’ [14]. Stylised subgenres often spring from artist’s attempting to fulfil a need, a prime example being punk poets searching for political clarity and cathartic release in the 1980s, and Instapoetry is arguably fulfilling an emotional need for audiences who are searching for simplistic, relatable and emotionally empowering content online, perhaps for a cathartic release of their own.

Publishing houses are taking notice of these authors with their large, pre-established audiences and are publishing physical collections with a growing frequency. Andrews McMeel, who have published collections by Rupi Kaur, Amanda Lovelace and Lang Leav, demonstrate this, and they claim to have ‘an uncanny ability to tap into the zeitgeist of popular culture to identify, nurture and share fresh, new voices that are somewhat off the beaten path’, suggesting that the work of these Instapoets are exactly what this publisher is looking for [15]. Besides this, poets including Hollie McNish and the otherwise anonymous Atticus go on tour with their work, performing live spoken word events and drawing in wider audiences, or conversely, showing their pre-existing audience another corner of the poetry world, helping to bring a resurgence to the poetry scene, publishing industry, and market.

Now more than ever, poets and their poetry are ‘diversifying’ along with their audience and methods of consumption, and it is safe to assume that, for as long as there are poets online with accessible content, the poetry market will continue to grow, especially as there are reports supporting ‘an emerging market for writers… that’s taken shape on Twitter, Instagram, and other networks’ [16],[17].

SOURCES

[1] The Independent, ‘First Lines of Oldest Epic Poem Found’ (November 16, 1998) https://www.independent.co.uk/news/first-lines-of-oldest-epic-poem-found-1185270.html [accessed March 2020].

[2] Statista, ‘Number of monthly active Instagram users from January 2013 to June 2018’

https://www.statista.com/statistics/253577/number-of-monthly-active-instagram-users/ [accessed March 2020].

[3] Simon & Shuster, the sun and her flowers by Rupi Kaur, ‘About the Author’ https://www.simonandschuster.ca/books/The-Sun-and-Her-Flowers/Rupi-Kaur/9781501175275 [accessed March 2020].

[4] Faith, Hill, Karen, Yuan, ‘How Instagram Saved Poetry, Social media is turning an art form into an industry’, The Atlantic (October 15, 2018) https://www.theatlantic.com/technology/archive/2018/10/rupi-kaur-instagram-poet-entrepreneur/572746/ [accessed March 2020].

[5] Simon & Shuster.

[6] Rebecca Watts, ‘The Cult of the Noble Amateur’, PN Review (PN Review 239, Volume 44, Number 3, January-February 2018) https://www.pnreview.co.uk/cgi-bin/scribe?item_id=10090 [accessed March 2020].

[7] Natasha, Onwuemezi, ‘Poetry sales are booming, LBF hears’ The Bookseller (April 13, 2018) https://www.thebookseller.com/news/poetry-summit-766826 [accessed March 2020].

[8] Donna, Ferguson, ‘Poetry sales soar as political millennials search for clarity’ The Guardian (January 21, 2019) https://www.theguardian.com/books/2019/jan/21/poetry-sales-soar-as-political-millennials-search-for-clarity [accessed March 2020].

[9] Ferguson, The Guardian

[10] Statista, ‘Distribution of Instagram users worldwide as of January 2020, by age and gender’ https://www.statista.com/statistics/248769/age-distribution-of-worldwide-instagram-users/ [accessed March 2020].

[11] Carl, Wilson, ‘Why Rupi Kaur and Her Peers Are the Most Popular Poets in the World’, The New York Times (December 15, 2017) https://www.nytimes.com/2017/12/15/books/review/rupi-kaur-instapoets.html [accessed March 2020].

[12] Priya, Khaira-Hanks, ‘Rupi Kaur: the inevitable backlash against Instagram's favourite poet’, The Guardian (October 4, 2017) https://www.theguardian.com/books/booksblog/2017/oct/04/rupi-kaur-instapoets-the-sun-and-her-flowers [accessed March 2020].

[13] Anna, Leszkiewicz, ‘Why are we so worried about “Instapoetry”?’ New Statesman (March 6, 2019) https://www.newstatesman.com/culture/books/2019/03/instapoetry-rupi-kaur-genre-rm-drake-rh-sin-atticus-hollie-mcnish [accessed March 2020].

[14] Vanessa, Thorpe, ‘Sell-out festivals and book sales up … it’s poetry’s renaissance’, The Guardian (March 26, 2017) https://www.theguardian.com/books/2017/mar/26/poetry-renaissance-festivals-book-sales-john-cooper-clarke-kate-tempest-henry-normal-nottingham [accessed March 2020].

[15] Andrews McMeel Universal, ‘About’ https://www.andrewsmcmeel.com/about/ [accessed March 2020].

[16] Annabel, Robinson, ‘Poetry market is growing as audiences – and poets - diversify: Verdict from the first-ever Poetry Summit at London Book Fair’, FMcM (April 13, 2018) http://fmcm.co.uk/news/2018/4/13/poetry-market-is-growing-as-audiences-and-poets-diversify-verdict-from-the-first-ever-poetry-summit-at-london-book-fair [accessed March 2020].

[17] Submittable, ‘A Decade of Change: Publishing Industry Trends in 7 Charts’ (September 12, 2019) https://blog.submittable.com/publishing-industry-trends/ [accessed March 2020].

Words by Emily Gough

Image from Unsplash