Conversation with James Holden: War Veteran and Grandfather

James Norman Holden thinks he’s the oldest man alive.

‘How are you?’ I ask.

‘Old and bored,’ he replies.

Of course, he’s only ninety-five. Like many people, he’s spent the last few months in isolation. Despite following the advice, he’s starting to feel lonely, a feeling he’s not used to in normal times.

Before coronavirus came in to public consciousness in the UK, I went to visit him in his flat on a visit home from university. As I walked in to the flat, I turned the corner into the kitchen, expecting the worst. The plates piled high. Old pits of tissue floundered on the kitchen countertop: mould, wedged between two plates. I gave him a hug and emptied my bag onto the counter. Mushrooms, eggs on toast, should be easy enough. I began to cook.

At his ripe age, my grandfather is naturally an active, social man. Pre coronavirus hit, he would play bridge with his pals on a Wednesday and go fishing in the summer.

‘I’m not lonely,’ he told me, as we started our conversation. He had recently undergone cataract surgery and, according to my father, was the star of the show at the hospital. Nurses fawned over him, asking to be invited over for his special G&T.

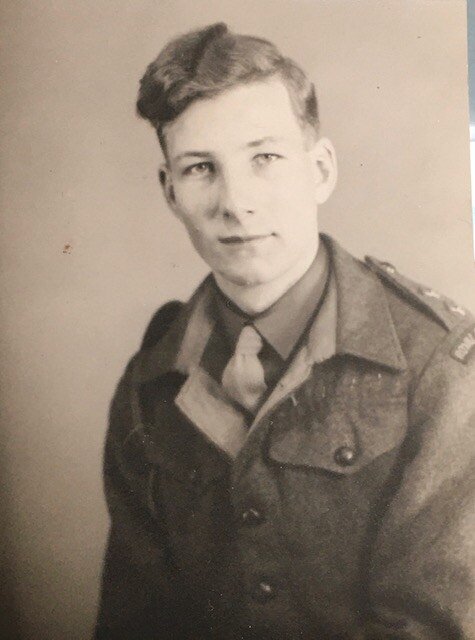

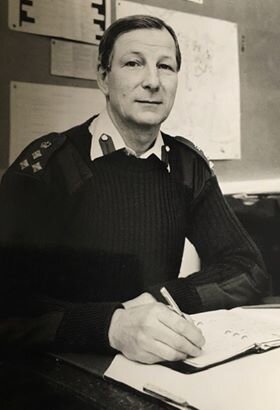

My grandfather is a self-proclaimed dustbin. Throughout my life, he has scolded me for leaving any leftovers, and had two packets of crisps before dinner. He was born on November 19th 1924 in Ludlow, Shropshire. There, he lived with his mother, father and his younger brother, Yan, who has since passed away. His father was a civil engineer, a job my grandfather himself would later undertake in the British Army. My grandfather married later in life, at 36, and went on to have three children, my father included. He now resides in a modest flat in Bath. The man is a mountain of knowledge, experience and entertainment. And at ninety-five, you’d expect nothing less.

I was pleased when my grandfather told me he had ‘quite a happy upbringing,’ despite growing up in the aftermath of the First World War, and the beginning of the Second. Though he lived in the countryside, the drum of war was very much alive.

“You could hear the German bombers overhead…it had a particular different sound from British aircraft. One of the German aircraft had been hit by anti-aircraft and had turned for home, and it hadn’t dropped its bomb…so they were limping home, and his bombs were dropped in a field. Didn’t do any damage at all, but made a very big hole.”

During this time, my grandfather, and his village, came across numbers of evacuees coming in from larger towns and cities. Though his family home did not have the space to shelter and evacuee themselves, my grandfather does still have stories from that time. The town was shocked when they arrived, he says, and even more stunned that many of the evacuees did not know that milk came from a cow. The village was home for just some of the 3.5 million people evacuated to the country throughout the Second World War. The first evacuation of 1.5 million people was in 1939. Children carried gas masks, and identity cards along with a limited amount of clothes and essential supplies.

Until the age of seventeen, my grandfather continued to live in his home village. However, in 1941, he joined the war effort. Seventy-six years later, in 2017, my grandfather was awarded the highest honour for military service in France: the Legion of Honour. During our interview, I asked if I could see it, along with his other medals. As I rooted through his draw as per his instruction, I came across not only my grandfather’s medals, but also those of his father, my great grandfather, for his service in the First World War. I’m struck by how much they both achieved. Among the medals were the Victorian Cross and the Defence medal. Their achievements are incredible.

James Norton Holden’s WWI medals

James Norton Holden’s WWII medals

In 1951, as Britain started to rebuild itself after the war, my grandfather worked in London.

‘It was a really quite extraordinary era. Nothing was a bit surprising to my generation. There were great piles of rubble from the blitz.’ Life wasn’t all doom and gloom, however, especially for a bachelor.

‘It was quite a good nightlife…You could go to nightclubs, and you could dance.’

During this time, in an effort to keep spirits and moral high, the Festival of Britain was opened, celebrating Britain and everything it had to offer.

It’s difficult for me to imagine my grandfather defending my country. But he fought. He fought for us.

Eventually, I piled the food onto two plates, proud that I had poached an egg to perfection.

Eventually, our attention turns to my grandma, my grandfather’s late wife. The two of them married on July 23rd in 1960 at Borne Abbey, Lincolnshire. Thereafter, they travelled extensively for my grandfather’s army job.

‘Where is your favourite place? I asked him.

Between 1960 and ’62, my grandfather and mother lived in Paris, where my grandad was posted. He began to speak in French and I was shocked at how fluent he was, even today. He told me that, although he loved it there, my grandmother had other opinions, believing the French to be arrogant towards those who were not fluent in French.

Despite first impressions, Elizabeth Mary Holiday, later Holden, was far from your conventional housewife. I learned that she once helped to design a large, successful clothing brand for Aristocratic families, and I’m proud she was a businesswoman at heart.

My grandfather and mother loved each other very much, and I don’t need to ask my grandad to know that it was hard when she died of cancer in 2001. I don’t have any memory of her, but I’ve heard she was a character, running away from school as a child. She was always ‘very good with people,’ my grandad told me. She would always be the one to ensure they did not lose touch with friends. She was a conversationalist, and a social butterfly. I now know where I get my extrovert side. My grandfather has lived without her for nearly twenty years. He’s counts himself quite unlucky on that front.

As we rounded up at the end of our conversation, I piled away the plates from dinner and reloaded the dishwasher, ignoring my grandfather as he told me he would do it later. When he wasn’t not looking, I secretly binned the mouldy bread, replacing it with a fresh loaf I bought that day. We hugged, and I said my goodbyes.

As I sit at my computer today, I have just finished a call with my grandfather. He is bored, and asks if he can have another bottle of gin when my mother next goes to drop him off some food. I know, like so many others, he looks forward to the day he can see us properly again.

by Grace Holden