Writing Fiction in a Post-Truth World

Can our relationship with fiction help us make sense of a post-truth society?

It’s been over a year since Oxford Dictionaries named ‘Post-Truth’ as their international word of the year. Defined as ‘relating to or denoting circumstances in which objective facts are less influential in shaping public opinion than appeals to emotion and personal belief’, it came in the wake of a seismic shift in politics following Brexit and the American election of Donald Trump. We now live in a reality where facts are only as valued as much as they are believed, and fictions can be spun into truths if they’re trusted by enough people.

So where does that leave actual fiction?

I’ve compiled a list of books focus on issues of truth, perspective and reality in fiction:

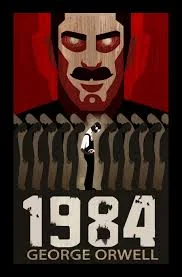

1984 by George Orwell –

Dystopian novels have seen a major rise in sales since the emergence of post-truth politics, and 1984 is chief among them. Depicting a dystopian society governed by a totalitarian regime, it’s a book that deals with the issues of complete governmental control of facts, language and thought. Indeed, the popularisation of the term ‘alternative facts’ by the Trump administration has been compared to the Orwellian terms ‘newspeak’ and ‘doublethink’. As a work of speculative fiction, it works well as a representation of the consequences of having a government that chooses to dismiss facts in favour of their own manipulative fiction.

The Handmaid’s Tale by Margaret Atwood –

Another work of speculative fiction, Atwood’s novel focuses specifically on the effect a suppressive authoritarian government would have on the experiences of women. While the ideas of information manipulation are much subtler than those presented in 1984, it can still be read as a cautionary tale of the potential outcomes of the manipulation of facts by a government, especially since Atwood has said that everything she wrote in the novel is based on some elements of truth from real life.

The Hate U Give by Angie Thomas –

Rather than dealing with the possible future effects of a post-truth world, The Hate U Give reflects the harsh realities of the results of factual manipulation that people face today. Telling the story of Starr, a young black woman who witnesses the murder of her friend at the hands of a police officer, it’s a book which highlights the struggle for truth that minorities have to fight for over those in power. Lacking the more science-fiction elements of the two other books, The Hate U Give is a much more sobering story for its portrayal of current post-truth consequences that people have been living with for much longer than the phrase.

Life of Pi by Yann Martel –

A book that’s significantly lighter than the ones listed above, it tells the story of a young man who is trapped for a year at sea with a tiger. Told alternately from the point of view of Pi at sea and a journalist who is interviewing him later on in life, it makes an interesting point about the importance and relevance of truth. Without giving too much away, the text is an example of an unreliable narrator. Towards the end of the story, Pi asks the insurance men interviewing him, after telling them two versions of the event, ‘“since it makes no difference to you and you can’t prove the question either way, which story do you prefer?’”. He’s essentially asking whether it matters what truth is told if the outcome is the same. While not as inherently political as the other books, it still serves as an interesting alternate argument regarding the nature of truth in fiction.

A Million Little Pieces by James Frey –

In relation to truth in fiction, this book isn’t one which deals with the theme of truth directly but contextually. Initially listed as a memoir about the author’s struggles with drug addiction, it was a New York Times bestseller and chosen as part of Oprah’s Book Club. However, it later emerged that parts of the book never actually happened, and that the author had exaggerated or fictionalised many of the events for dramatic effect. This book is interesting in that Frey initially pitched the book as a work of fiction, but his publishers persuaded him to market it as a memoir as they believed it would sell better. While written before the popularisation of ‘post-truth’, it still serves as a good example of whether the truth behind it impacts the power of a memoir’s story.

by Seren Livie